Meraka Telehealth:Project Chapter: Difference between revisions

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

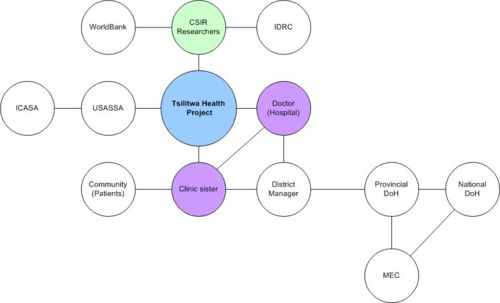

Boundary partners are those individuals, groups, and organizations with whom the program interacts directly and with whom the program anticipates opportunities for influence. | Boundary partners are those individuals, groups, and organizations with whom the program interacts directly and with whom the program anticipates opportunities for influence. | ||

[[Image:Boundary_Partner_Map.jpg|thumb| | [[Image:Boundary_Partner_Map.jpg|thumb|left|500px|Boundary Partner Map]] | ||

Outcomes have been assigned to each boundary partner & progress markers are used to monitor behavioural changes of boundary partners in achieving the desired outcome. | Outcomes have been assigned to each boundary partner & progress markers are used to monitor behavioural changes of boundary partners in achieving the desired outcome. | ||

Revision as of 16:09, 10 July 2007

FMFI Telehealth Project in Tsilitwa, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa

| Researchers: | Chris Morris (cmorris[@]csir.co.za) |

| Ajay Makan (amakan[@]csir.co.za) |

Background to the problem

The high unemployment rate in the Eastern Cape contributes to poverty. For example, 87% of the population in OR Tambo and Alfred Nzo district municipalities earn less than R800 per month. Poverty and the rurality of the Eastern Cape create a high dependency on public health services.

67% of communities live in rural areas in the Eastern Cape where harsh weather conditions, poor road and telecommunications infrastructure, and the lack of public transport have a direct impact on the delivering of healthcare services.

This situation is due to poor infrastructure and isolation of rural clinics. The workload is also increasing due to HIV/AIDS epidemic and thus the need for specialized advice or consultation or second opinion.

Lack of transport, bad roads makes referring of patients sometimes impossible thus treatment of patient in the community is the only option.

Lack of telecommunication, particularly in rural areas, makes proper referring of patients difficult and costs patients time and money to travel. Lack of access to training and Continual Medical Education (CME) severly limits healthworker development in rural areas and keeps healthcare workers away from the rural health centres.

A major challenge in the Eastern Cape is the drain of healthcare professionals from the rural communities to the more developed urban centres. Professional isolation from their peers contributes to the difficulty in attracting and retaining qualified staff in rural areas. Traditionally health professionals and managers have to travel long distances for meetings and knowledge transfer. This also results in high cost and loss of productivity.

Specialised care is very scarce in the Eastern Cape. There are only 2 dermatologists, 2 radiologists, 2 oncologists and no oral health specialists in the public service.

Due to the lack of telecommunications infrastructure in rural areas, wifi is seen as a potential solution to meet the needs of rural connectivity. However, the use of wifi in the 2.4GHz ISM band (which is license free internationally) is forbidden where it cuts across public boundaries and where the power emission of the antenna exceeds 100mWatts. So the challenge of this project is to pilot the use of wifi in order to demonstrate to government how low-cost technologies such as wifi can be used to meet the communication needs of deep rural communities.

The Tsilitwa Project

The tele-health application developed in Tsilitwa in 2001 formed part of the Department of Science and Technology’s Innovation Fund project entitled “Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) in support of communities in deep rural areas”.

The community leader from Tsilitwa approached the CSIR in 1999 to draft a funding proposal after having visited a similar CSIR project at Lubisi. The request was for Information Communication Technology (ICT) to support health, education, agriculture and small business.

The project involved the two communities of Tsilitwa and Sulenkama that were geographically separated by a hill preventing direct access between the villages and requiring people to travel the 15km by a very poor dirt road where the public transport was unreliable. These towns are approximately 100km north east of Umtata. The two villages are typical of the former Transkei area and to this day have no electricity to homes, no running water, dirt roads and no telecommunications. The villages are spread out and people build mud-block houses with thatch roofs or corrugated iron. Some houses are constructed from brick with tile roofs. The population is mostly unemployed totalling approximately 2000 in each village.

The community facilities in Tsilitwa include a pre-fabricated clinic and technical school that, through the efforts of the headmaster, is electrified. The clinic ran on solar power until 2002 when it was electrified. The village of Sulenkama some 15km away has more infrastructure boasting a 200 bed community hospital called Nessie Knight with electricity (generator back-up) and 3 DECT telephone lines. The telephones do not usually work and the hospital staff rely on their personal cell phones to call Mthatha for an ambulance.

Regulatory Environment (South Africa)

It is important that the project team have a clear understanding of the regulatory environment in order to be able to use the research results as inputs for future policy. Regulation regarding WiFi

- WiFi networks are allowed when:

- The network is deployed on a single site

- Signals may only traverse short distance; EIRP not to exceed 100 milliWatts

- No interference to users of other ISM equipment or other frequency bands may be caused

- The network must be confined to computer systems of the same user

- For community based networks a license is needed; either a PTN (Private Telecommunications Network) or VANS (Value-Added Network Service) license. The latter is needed when the network is connected to the Internet, and Internet services are provided

- Self provision has been an issue for long, but likely with the Electronic Communications Act (ECA), self provision will be allowed [need to check this]

- The regulatory framework surrounding WiFi deployment nevertheless remains complicated, and due to quick changes of staff at the regulator, applications for licenses could take long.

In order for community owned networks to be legally pursued, the regulator requires such projects to obtain both a PSTN as well as VANS license and the deployment of facilities dictates that the telecommunications facilities must be that belonging to Telkom or the SNO. However, the issue of self-provisioning remains a grey area open to interpretation. Under the ECA a class license would be needed by FMFI partners for both infrastructure and services, but the use of WiFi is still hamstrung by the control on power levels and crossing public boundaries. It is suggested that the FMFI partners continue to lobby government for a regulatory relaxation for the use of WiFi across public boundaries in rural areas for use in non-commercial sectors such as health and education.

Implementation Process

This project’s aim was to develop and implement an innovative communications infrastructure that was independent of the State telecommunication utility companies, and to develop capacity within the community involved, with appropriate information content, to support sustainable development in rural areas.

The project involved the two communities of Tsilitwa and Sulenkama that were geographically separated by a “koppie” preventing direct access between the villages and requiring people to travel the 15km by dirt road. Sulenkama is approximately 100km north west of Umtata.

The two villages are typical of the former Transkei area and to this day have no electricity to homes, no running water, dirt roads and no telecommunications. The villages are spread out and people build mud-block houses with thatch roofs or corrugated iron. Some houses are constructed from brick with tile roofs. The population is mostly unemployed totaling approximately 2000 in each village.

The community facilities in Tsilitwa include a pre-fabricated clinic and technical school that, through the efforts of the headmaster, is electrified. The clinic ran on solar power until 2002 when it was electrified. The village of Sulenkama some 15km away has more infrastructure boasting a 200 bed community hospital called Nessie Knight with electricity (generator back-up) and 3 DECT telephone lines. The telephones do not usually work and the hospital staff rely on their personal cell phones to call Umtata for an ambulance.

The hospital is run by highly dedicated staff and matron Buli Buli has been running the place for 15 years. In the last 4 years there was only one doctor, a contracted Cuban doctor named Dr Noel, servicing the community. He did have support from an intern named Dr Thomas for one year. Reasons given for the lack of doctors at Nessie Knight are the general shortage of doctors in the province, poor roads to the hospital, general isolation and no communications (internet).

The infrastructure implemented during the DACST funding included an MPCC at Tsilitwa and Sulenkama, PC network at the Tsilitwa school, a wifi network connecting Sulenkama hospital and police station to a number of sites in Tsilitwa including the clinic, school and the MPCC. Each of these sites was connected by means of VOIP. The Tsilitwa clinic was linked to the Sulenkama hospital with a web-cam to facilitate tele-consultation between the clinic sister and doctor at the hospital. In addition, e-mail was piloted at the clinic using a GSM modem as cellular coverage was introduced in the area. The clinic sister was provided with a digital camera that was then used to capture pictures of patients with skin disorders or wounds. The images were then sent to a specialist in Umtata for diagnoses and advice.

In December 2002 the MEC Health Dr Goqwana visited the project on World HIV/AIDS Day and was able to diagnose a patient from the Sulenkama hospital using the technology. The MEC requested more clinics be connected using the technology.

Having created awareness of the project at a number of conferences including Acacia 2003, we needed to develop the funding plan to continue at Tsilitwa and with the Department of Health.

In 2003 we were successful in winning funding from the World Bank Development Marketplace that funded the expansion of the network to other clinics around Tsilitwa. In addition, an application was made to the Universal Service Agency for sponsorship of a VSAT to provide internet and e-mail connectivity to the Sulenkama/Tsilitwa cluster. This is imperitive to continue with the tele-dermatology already piloted at Tsilitwa through the use of GSM. (The GSM was piloted for a year and then discontinued due to high running costs).

An MOU was signed between the USA, Department of Health and the CSIR for the implementation of the VSAT and ongoing support.

A continuing thorn in the side of the project was the issue of a license for the use of WiFi. It has been interesting to note the changes taking place in the regulatory landscape with respect to WiFi and at the African WiFi conference in 2004, a representative of ICASA indicated a willingness to assist with facilitating the use of WiFi in tribal lands.

The CSIR met with the regulator and issues of tribal and contiguous land and municipal PTN licenses were discussed. The CSIR are currently developing a strategy for use of WiFi in the Eastern Cape that includes applying for a spectrum test license and also ongoing discussions with Sentech and the possible use of their license.

Towards the end of 2004 the Minister of Communications awarded a license to 4 BEE companies to operate telecommunication services in under serviced areas. These Under Service Area Licensees, USALs, have been funded for a period of 3 years through the Universal Service Agency. At the award ceremony of the USAL contact was made with the USAL for OR Thambo, Ilizwi Telecommunications. Discussions took place and a site visit to the pilot project in Tsilitwa was made. The significance of this relationship is the use of the USAL license for providing wifi services in OR Thambo and the extension of the USAL services to include health and education.

Research Methodology

Outcome Mapping - Intentional design

A key objective of the FMFI project is to research social issues, the user interface and context of “first inch”, changes in behaviour in the use of ICTs – how the use of ICTs has changes community life. As a result, we identified the need for a methodology that supported a participatory approach for planning, monitoring and evaluation because many project stakeholders are involved in the planning, monitoring and evaluation of the project as beneficiaries and stakeholders.

User needs – application of the OM process

This section explores the Tsilitwa programme using the Intentional Design sub-headings of the Outcome Mapping methodology.

Vision

To enhance rural healthcare by using innovative low-cost ICTs, with capacity building, in order to link the clinic sister to health specialists.

Mission

To pilot WiFi technologies in deep rural areas to create a communications platform for the development of simple healthcare applications for rural clinics that are scalable and replicable.

To demonstrate to government how the use of low-cost communications technology can help promote development in underserviced areas through building local ICT capacity for enhanced healthcare and education. The results of this research will be used to inform policy in health and education and seek to influence telecommunications regulations.

To realise this vision, different mission aspects had to be dealt with. The approach to the mission involves:

- Gathering political support

- Establishing partnerships

- Constructing an appropriate solution

- Expanding the reach of the programme

- Regulatory endorsement

- Affordability

- Sustainability

Boundary Partners and Outcome Challenges

Boundary partners are those individuals, groups, and organizations with whom the program interacts directly and with whom the program anticipates opportunities for influence.

Outcomes have been assigned to each boundary partner & progress markers are used to monitor behavioural changes of boundary partners in achieving the desired outcome.